=SOLD= 2302:: Boogher v. Roach, 12 App. D.C. 477 (1898) April 4, 1898 · Court of Appeals

2302:: Boogher v. Roach, 12 App. D.C. 477 (1898) April 4, 1898 · Court of Appeals.

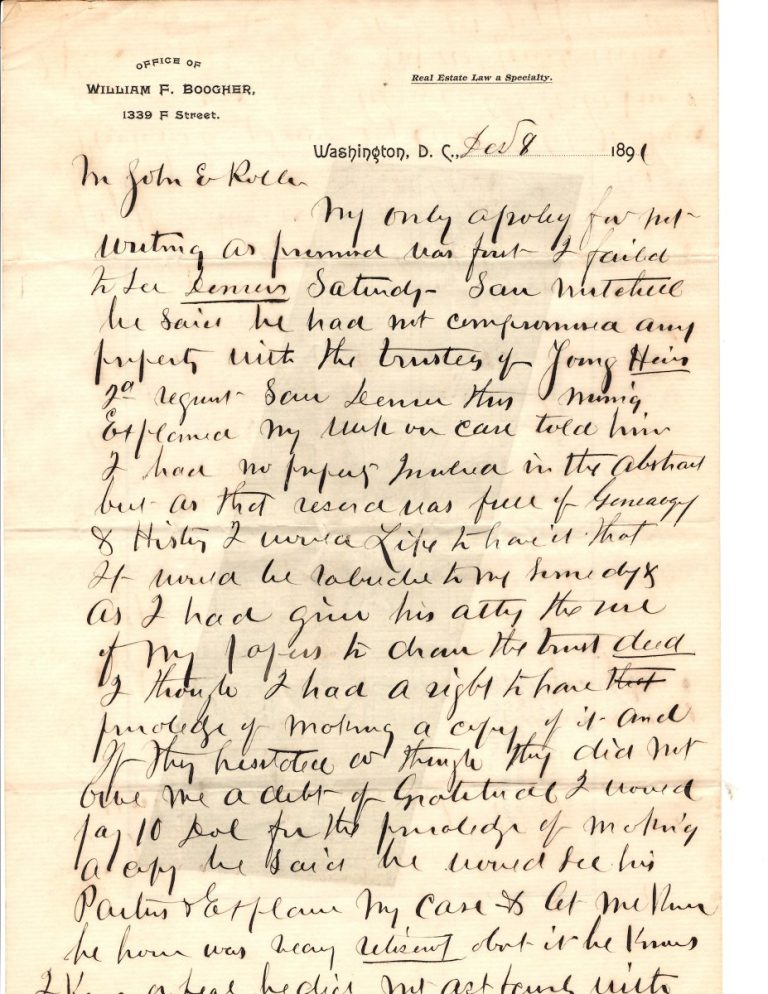

Document: Letter dated 1891

THIS IS A Hand-written letterhead, consisting of two pages, written in cursive ink one one side by William F. Boogher the complainant, who described himself as a “title searcher, conveyancer, and genealogist.”

Other Surnames Mentioned: Roach, Weaver, Young, Walter, Wheeler, Somers, Miller, Wilson, Denver.

One-sided letterhead. Map on verso featuring the Jamaica Tract in Washington, D.C.

Document’s Dimensions: 11½”H by about 8″W

…………………………………………………………………………………..

sold on eBay $15 on NOV 23rd 2021

…………………………………………………………………………………..

Boogher v. Roach, 12 App. D.C. 477 (1898)

April 4, 1898 · Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia · No. 766

12 App. D.C. 477

BOOGHER

v.

ROACH

Contracts ; Assignment.

Where a person having a contract with claimants of real estate to establish their claims, he paying all expenses and to receive a per centage of the value of the property recovered, sells one-half of his interost in the contract to another person, with the assent of the trustee for the heirs, and then fails to perform his contract with the claimants, such other person is not entitled to reimbursement out of a fund realized from a settlement of some of the claims for the amount paid by him for the half interest, or for services rendered the trustee or his successors.

Submitted March 10, 1898.

Hearing on an appeal by the complainant from a decree dismissing a bill in equity to charge a trust fund with payment of advances and for services claimed to have been rendered.

Affirmed.

The facts are sufficiently stated in the opinion.

*478 Mr. John E. Roller for the appellant:

1. Every trust estate must bear the expenses of its administration. This is the general principle. Trustees v. Greenhow, 105 U. S. 532; Railroad v. Pettus, 113 U. S. 122.

2. Where one of many parties having a common interest in the trust fund, at his own expense takes proceedings to. .•save it from destruction, or for. its preservation, or to restore it for the purposes of the trust, he is entitled to reimbursement either out of the fund itself or by contribution from the others. Hobbs v. McClain, 117 U. S. 582.

3. Whatever expenses are legitimately incurred in distribution are chargeable upon the property. The trustee is •entitled to be allowed, as against the estate, not only all payments expressly authorized by the trust itself, but all expenses reasonably necessary for the security, protection and preservation of the trust property, or for the prevention of the failure of the trust. The property is itself pledged for the payment of the debt and not simply its rents and profits. 2 Pom. Eq. Jur. Sec. 1085; Gisborn v. Insurance Co., 142 U. S. 326.

Mr. Franklin H. Mackey and Mr. Walter C. Glephane for the appellee.

Mr. Justice Shepard

delivered the opinion of the Court:

This is an appeal from a decree dismissing a bill filed by the appellant, William F. Boogher, against J. L. Weaver, Thomas W. Roach, and John H. Walter, surviving trustee, to recover certain sums and advances alleged to be due under contract and for special services.

Roach and Walter answered the bill. Weaver was cited by publication, but did not appear.

It appears that Thomas W. Roach was one of the numerous heirs-at-law of one Abraham Young, and with others maintained a claim by descent from said Young to certain parcels of land in the District. In connection with this *479claim, Roach and others entered into the following contract .with J. L. Weaver:

“Ligonter, Indiana, October 29, 1888.

“This is to certify that we hereby employ J. L. Weaver as our attorney to procure for us any and all interest we may have in the estates of Abraham Young, John Young, Elizabeth Wheeler, and Elizabeth Roach, or other estates in the city of Washington, District of Columbia, or county of Washington.

“The said Weaver may employ any attorney he desires at his own expense. He is to use all possible diligence and means to procure the said property. He is to pay his own expenses or any expenses necessary to procure the said property except taxes or liens on said property or redemption fees, which we agree to pay if necessary to obtain the said property; and we agree to pay the said Weaver ten per cent, of the value of said property obtained for us, whether it be a part or all, the said ten per cent, to be paid in cash, or as may be otherwise agreed upon, upon the amounts as fast as obtained and disposed of at the value of the property when disposed of.

“(Signed) Thomas W. Roach,

“ J. L. Weaver,

“ Mahlon F. Roach,

“ James A. Roach,

AND OTHERS.

“(Marginal Note.) — I agree to furnish and advance sucb taxes and redemption fees as are necessary to be furnished by the heirs of James Roach, they to pay them back to me when property is sold, with reasonable rate of interest.

“(Signed) J. L. Weaver.”

All the parties lived in Indiana. Weaver was not a lawyer. He seems to have been a kind of broker or agent of such claims. At the time of this contract Thomas W. Roach was also acting as trustee under deeds from some of the heirs of said Abraham Young, which deeds, it was *480alleged, were defective, and were substituted by others made April 1, 1890.

Weaver came to Washington, where he met with the complainant, William F. Boogher, who describes himself as a “title searcher, conveyancer and genealogist.” On June 14, 1889, he entered into a contract with Boogher, the material parts of which, after reciting the employment of Weaver, as aforesaid, read as follows:

“And whereas said Weaver has expended already large sums of money in preparation of said case, now this agreement witnesseth, that for and in consideration of the payment of one thousand dollars by the said Boogher, party of the second part, to the said party of the first part, the receipt of which is hereby acknowledged, does by the presents hereby convey, assign and transfer to the said Boogher, party of the second part, one-half of all his interest in the fees as attorney, or otherwise by contract or agreement, heretofore made or that may be hereafter made with any or all. of the heirs of William Young, Abraham Young, Elizabeth Wheeler, John Young, Susanna Somers and Elizabeth Roach, or the trustee, Thomas W. Roach, or his successor, the said one-half interest of any and all monies due or to become due to the party of the first part.

“And the said J. L. Weaver further agrees to use due diligence to have the trustee increase his fees from ten per cent, to twenty per cent.

• “And further the parties of the first and second parts mutually agree to give the necessary attention to the settlement of the estate and to share equally in the expense and profit from this date, and that the said W. F. Boogher, party of the second part, is not to be held responsible for any of the expenses incurred prior to this date.

“And it is further understood in strict compliance with the agreement with the trustee, Roach, that all expenses are to be paid back to the party of the first and second parts out ,of the first money realized from said estate. And it is further agreed that the said W. F. Boogher, party of the second part, *481shall receive his one-half interest aforesaid direct from the trustee, regardless of what the party of the first part may have already paid out, or may hereafter be entitled to as his portion of said fee.”

This contract bears the following endorsement:

“I hereby ratify the above contract.

“(Signed) Thomas W. Roach, Trustee.”

And witnessed by Charles W. Miller.

This endorsement was not denied by Roach in his answer, but was referred to therein in words substantially admitting it. In his testimony he denies its execution. Charles W. Miller, whose name appears as a witness thereto, testified that he had no recollection of witnessing the endorsement, and that the signature purporting to be his was not genuine; but he further said that he was familiar with Roach’s signature, and pronounced it genuine. Boogher paid Weaver $600 of the $1,000 promised in the contract; but stopped the payment of a check given for the remainder, and the same was never paid. All parties agree that Weaver failed to perform his contract.

Boogher evidently did a great deal of work in discovering the names, degree of kinship and residences of the numerous descendants of Abraham Young, as well as in hunting up the lands to which it was thought they could successfully assert title. Although quite an expert as a “genealogist,” he did not claim to be a lawyer or expect to represent the parties in that capacity. Boogher had frequent interviews with Roach, who availed himself of information given by Boogher.

Some of the heirs of Young, who had joined Thomas W. Roach in the contract with Weaver, afterwards, on November 18, 1890, executed a conveyance to Henry D. Wilson, passing their interest to him, in trust, to recover the sums, compromise, sell, and so forth, with power of substitution.

On account of defects in the first conveyance by some of the Young heirs to Thomas W. Roach, the latter procured *482two other deeds, which were signed by many of them, representing claims to about two-fifths of the whole title. These were dated, respectively, April 1 and July 30, 3890, and conveyed the title upon the same trusts and with the same powers substantially as in the Wilson trust deed, above mentioned.

Under the power of substitution therein, Thomas W. Roach, trustee, conveyed the same upon the same trusts to James W. Denver and John H. Walter, as joint tenants. Denver soon died, and the trust has been administered by Walter, the survivor.

Boogher was aware of this substitution, and furnished his descriptions and statements of heirs and property to an attorney, for the preparation of the necessary deed. It appears, however, that this deed was rejected by Walter, who had another prepared and executed by Roach.

Walter, who is himself an expert searcher of titles and “genealogist,” admits the use of Boogher’s information; but claims to have done a great deal of work in that line himself, and to have had nearly, if not quite, as much information as Boogher.

On January 6, 1891, Wilson made a similar conveyance to Denver and Walter.

Some recoveries and compromises have been made by Walter, and he has funds of the trust in his hands to an amount not shown. ■

Boogher claims reimbursement • for his $800 paid to Weaver under his contract above set out, ten per cent, of the fund realized by Walter, and the sum of $2,000 for his special services rendered in furnishing the information to Weaver, Roach, Denver and Walter. All this he alleges to be a charge against the trust fund. His prayers are that Walter be restrained from disposing of the fund, and required to render an account thereof; that discovery be made by Roach and Weaver of sums received by them from the trust fund; that the contracts set out be reformed, *483as the equities of the case may require, and enforced; and for general relief.

Passing by the apparently ehampertous nature, first, of the contract between Roach and others and Weaver, and, second, of that between Weaver and Boogher, which is the foundation of the suit, and assuming that the latter was in fact ratified by Roach, as trustee, we see no ground upon which Boogher can establish liability thereunder against the trust fund in the hands of Walter. The $600 paid to Weaver, of the $1,000 recited therein, was not to be expended on account of the trust or the interest of the parties represented by Roach, as trustee. It was a part of the consideration paid by Boogher to Weaver for the half interest in his contract with Roach and other heirs of Young. Possibly he may have a claim against Weaver on account of this payment; but certainly ho has none, either at law or in equity, against the other parties. That this money may have been advanced to Weaver on account of expenses incurred in the investigation of the claims is of no importance, if true, because, by the express terms of his contract, Weaver assumed the payment of all such charges in consideration of the interest that he was to receive.

Roach’s ratification of the contract between Weaver and Boogher did not change the terms of the original contract with Weaver. It can have no other effect than as evidence of the assent by Roach, as trustee, to the association of Boogher with Weaver.

Moreover, no claim of an interest secured by that contract can be enforced, because it is conceded by all parties that Weaver did not perform his part thereof. Shortly after he made his contract with Boogher he seems to have abandoned all pretence of performance. Nor did Boogher, after Weaver’s default, offer or undertake to perform the same, as he might have done, with the assent of Roach, which had, to that extent, been given by his assent to the contract between Boogher and Weaver.

*484The original instrument constituting Roach trustee for a part of those interested in the Young land claims, is not in the record; but it is conceded that it was defective in important particulars. In consequence of those defects, it was found important, if not necessary, to secure new deeds in trust from the heirs.

These were secured in two instruments under date of April 1, and July 10, 1890, respectively. Part of the new arrangement, also, was the plan to substitute Denver and Walter for Roach, in the administration of the trust.

This was acquiesced in by Boogher. The evidence shows that he rendered aid to Roach, and that his genealogical memoranda were of advantage to him and the substituted trustee in naming and locating the widely scattered heirs whose signatures were necessary to perfect the new arrangement.

Now, whilst the acceptance of these services might have entitled him to an action of assumpsit against Roach, and even against Denver and Walter, we entirely agree with the learned justice who presided at the hearing that his claim therefor can not be made a charge against the trust estate or fund. The services were not rendered to trustees in the administration of a trust and for the benefit of the makers and beneficiaries thereof, as was the case in Gisborn v. Charter Oak Insurance Co., 142 U. S. 326, the authority chiefly relied on by the appellant.

On the contrary, they were rendered to, and on behalf of, individuals engaged in procuring the creation of a trust for a purpose of their own. Doubtless these persons had some special contract with the heirs, whom they induced to execute the new trusts, looking to an interest in the proceeds of the lands expected to be recovered; but whether that be the case or not, the services of Boogher were rendered to them primarily and for their benefit.

Although these parties are before the court, there is nothing in either the allegations or the prayers of the bill to *485justify a court of equity in exercising jurisdiction of the claim against them individually. It is not necessary, therefore, to consider the question whether the complainant would not, in any event, be barred of relief by reason of laches in the assertion of his demand.

The decree will be affirmed, with costs. Affirmed.

USA 1891 c.Reference number: 2021.2302 sold

Click here to print.

go back